Random Politics & Religion #24

|

Random Politics & Religion #24

It just goes to show you that Jews do run the country. And Zuckerface would round us up in a internment camp and force us to like pictures of cats. All while hoarding is Jew gold. Not to be critical...

Of all my paranoid schizophrenic internet personas the "Jews are controlling everything" is my favorite.

fonewear said: » force us to like pictures of cats. You Ailurophobe  [Mod Edit: Officially rescued. - AnnaMolly] I like cats too but not in real life. Just pictures is fine.

The world (and this thread) would be in a much better place if we had more pictures of kittens.

[Mod Edit: Officially rescued. - AnnaMolly] /sends Kuwoobie a kitty

Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better.

The real question is if those cats voted for Hillary or Trump. I mean that is the level of dialogue I've come to expect and love here !

fonewear said: » Zuckerface wants a global income for everyone yet fails to give me money. I think we should boycott Facebook for real this time ! https://finance.yahoo.com/news/mark-zuckerberg-joins-silicon-valley-202800717.html Oh look another liberal elite telling other people what to do while conveniently excluding themselves. Liberals love to spend "other peoples money" even when they have plenty of their own. fonewear said: » The real question is if those cats voted for Hillary or Trump. I mean that is the level of dialogue I've come to expect and love here ! Well it voting in a US Election is the right of any global citizen, then why not extend that franchise to cute animals too? Isn't fun that rich people tend to be the ones that complain about income inequality. Yet don't know why people are poor to begin with ?

Asura.Vyre said: » Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better. <Reddster> Here's why you are wrong, and a stinky face. <Bluester> Yeah, well, your mom sleeps with more politicians than a Clinton. <Oklahoman> Duuuuuuur.... *Inserts kitten pics* *Love and Peace comes to the world for 14.95 seconds* Asura.Kingnobody said: » Asura.Vyre said: » Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better. <Reddster> Here's why you are wrong, and a stinky face. <Bluester> Yeah, well, your mom sleeps with more politicians than a Clinton. <Oklahoman> Duuuuuuur.... *Inserts kitten pics* *Love and Piece comes to the world for 14.95 seconds* Don't make me turn cats into a metaphor about how liberals like to drink milk and have their tummies rubbed ! Bahamut.Ravael said: » fonewear said: » Zuckerface wants a global income for everyone yet fails to give me money. I think we should boycott Facebook for real this time ! https://finance.yahoo.com/news/mark-zuckerberg-joins-silicon-valley-202800717.html Person A: We should all do (insert thing here). Person B: Then you should go first and set the example. Person A: No. fonewear said: » Asura.Kingnobody said: » Asura.Vyre said: » Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better. <Reddster> Here's why you are wrong, and a stinky face. <Bluester> Yeah, well, your mom sleeps with more politicians than a Clinton. <Oklahoman> Duuuuuuur.... *Inserts kitten pics* *Love and Piece comes to the world for 14.95 seconds* Don't make me turn cats into a metaphor about how liberals like to drink milk and have their tummies rubbed ! I gave this book to a radical turns out CNN read it also:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rules_for_Radicals "Power is not only what you have, but what the enemy thinks you have." Power is derived from 2 main sources – money and people. "Have-Nots" must build power from flesh and blood. "Never go outside the expertise of your people." It results in confusion, fear and retreat. Feeling secure adds to the backbone of anyone. "Whenever possible, go outside the expertise of the enemy." Look for ways to increase insecurity, anxiety and uncertainty. "Make the enemy live up to its own book of rules." If the rule is that every letter gets a reply, send 30,000 letters. You can kill them with this because no one can possibly obey all of their own rules. "Ridicule is man's most potent weapon." There is no defense. It's irrational. It's infuriating. It also works as a key pressure point to force the enemy into concessions. "A good tactic is one your people enjoy." They'll keep doing it without urging and come back to do more. They're doing their thing, and will even suggest better ones. "A tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag." Don't become old news. "Keep the pressure on. Never let up." Keep trying new things to keep the opposition off balance. As the opposition masters one approach, hit them from the flank with something new. "The threat is usually more terrifying than the thing itself." Imagination and ego can dream up many more consequences than any activist. "The major premise for tactics is the development of operations that will maintain a constant pressure upon the opposition." It is this unceasing pressure that results in the reactions from the opposition that are essential for the success of the campaign. "If you push a negative hard enough, it will push through and become a positive." Violence from the other side can win the public to your side because the public sympathizes with the underdog. "The price of a successful attack is a constructive alternative." Never let the enemy score points because you're caught without a solution to the problem. "Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it." Cut off the support network and isolate the target from sympathy. Go after people and not institutions; people hurt faster than institutions. Asura.Saevel said: » .... Did you know that there are several area's in the 9th circuits domain that are very conservative yet because of the 9th being located in San Francisco and being politically connected to California it's an extremely liberal court. There are some consertive counties west of the mountains too. But the vast majority of the population in the 9th's states are liberal Asura.Saevel said: » fonewear said: » Zuckerface wants a global income for everyone yet fails to give me money. I think we should boycott Facebook for real this time ! https://finance.yahoo.com/news/mark-zuckerberg-joins-silicon-valley-202800717.html Garuda.Chanti said: » Asura.Saevel said: » .... Did you know that there are several area's in the 9th circuits domain that are very conservative yet because of the 9th being located in San Francisco and being politically connected to California it's an extremely liberal court. There are some consertive counties west of the mountains too. But the vast majority of the population in the 9th's states are liberal Their actually not, just the majority who live in cities and vote are. Well that and California. California needs to be it's own district as it just overshadows everything else nearby. Asura.Vyre said: » Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better. Asura.Kingnobody said: » Asura.Vyre said: » Pictures of cats stuck in political thread. They deserve better. <Reddster> Here's why you are wrong, and a stinky face. <Bluester> Yeah, well, your mom sleeps with more politicians than a Clinton. <Oklahoman> Duuuuuuur.... *Inserts kitten pics* *Love and Peace comes to the world for 14.95 seconds* Our new slogan is "Oklahoma; We didn't elect a maskless luchador!" Clinton in her speech today made remarks about a full on assault on the truth. Clearly referring to someone aside from herself.

Then has a coughing fit and immediately blames allergys (after a day and a half on downpours. All with a straight face. For Pleebo, in hopes it will prove an earlier point.

On travel ban, judges reach 'Trump only' decision Sources are bad, unless they are heavily liberal biased. Quote: There's a glaring political divide in the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals decision to stop President Trump's revised executive order limiting entry into the U.S. for some people from a few terror-plagued Muslim-majority nations. The court ruled against the president by a solid 10 to 3 vote. All ten on the winning side were appointed by Presidents Barack Obama or Bill Clinton. All three on the losing side were appointed by Presidents George W. Bush or George H.W. Bush. If anything, the decision shows the value of a two-term presidency in shaping the courts. The 4th Circuit, once solidly conservative, is conservative no longer with six Obama appointees. Chief Judge Roger Gregory's majority decision is 79 pages long, but it boils down a single point: It doesn't matter whether the text of the Trump order is constitutional, because the president's previous statements about Muslims, made mostly during the campaign, prove that it is based in animus against a religion, and is therefore unconstitutional. Gregory made his case in a headline-grabbing opening paragraph, in which he declared that the executive order "in text speaks with vague words of national security, but in context drips with religious intolerance, animus, and discrimination." The majority's decision, as laid out by Gregory, suggests a mind-bending possibility: If the Trump executive order, every single word of it, were issued by another president who had not made such statements on the campaign trail, the court would find it constitutional. "There is no doubt that this is a Trump-only decision," said John Yoo, the Berkeley law professor who served in the George W. Bush Justice Department, in an email exchange Thursday. "The Fourth Circuit clearly says that the executive order is legal on its face because of its invocation of national security reasons. But the court refuses to apply the traditional deference to the president and Congress in immigration affairs because of Trump's statements both as a candidate and as president that -- it claims -- reveal he is acting in bad faith." At the heart of the issue is an argument over whether, in a matter like the Trump order, judges can look behind the plain text of the document to discern the author's motives. The debate in the Trump matter rests on two cases dating from the early 1970s: Lemon v. Kurtzman and Kleindienst v. Mandel. At its core, the new 4th Circuit decision is a group of Democratic-appointed judges saying "Lemon shows we are right," and a group of Republican-appointed judges saying "Mandel shows we are right." This is no place for in-depth legal analysis -- especially since I am not a lawyer -- but the short version is, Lemon was a 1971 case involving a state law in Pennsylvania which allowed some public money to go to private, that is, religious, schools. The Supreme Court struck down the law and established what some have called the Lemon test. For a law like Pennsylvania's to pass constitutional muster, the decision said, the government must show three things: 1) that the law has a "secular legislative purpose"; 2) that the "principal or primary effect" of the law "must not advance nor inhibit religion"; and 3) that the law "must not result in an 'excessive government entanglement' with religion." In his decision, Gregory said the Trump executive order was all about the first test, the "purpose" test. "Under the Lemon test's first prong, the government must show that the challenged action 'has a secular legislative purpose,'" Gregory wrote. "Accordingly the government must show that the challenged action has a secular purpose that is 'genuine, not a sham, and not merely secondary to a religious objective.'" Gregory then argued that Trump's campaign statements prove that the Trump executive action, whatever its stated concerns about national security, is in fact rooted in hatred for Muslims. At one point, Gregory seemed to concede that the order on its face might well be constitutional, and that is why he, Gregory, had to look beyond the text. "If we limited our purpose inquiry to review of the operation of a facially neutral order, we would be caught in an analytical loop, where the order would always survive scrutiny," Gregory wrote. "It is for this precise reason that when we attempt to discern purpose, we look to more than just the challenged action itself." By looking at Trump's statements, Gregory said, "it is evident" that the executive order "is likely motivated primarily by religion." That doesn't mean that the order has no national security purpose at all, just that "any such purpose is secondary to [the order's] religious purpose." So Gregory, and the rest of the court's Democratic appointees, ruled against the president. The reliance on the Lemon "purpose" test struck some experts as dead wrong. "Lemon shows again why this is a Trump-only case," wrote John Yoo. "The Supreme Court has all but overruled Lemon. It never follows the Lemon test anymore, because of its inherent unpredictability and vagueness. That the 4th Circuit turned to it here showed how far it would go to extend judicial power to stop Trump." On the other side, the dissenters -- the three Republican-appointed judges -- cited Kleindienst v. Mandel, a 1972 case that has the virtue of actually involving immigration. In that case, the attorney general denied entry into the U.S. of Ernest Mandel, a self-described "revolutionary Marxist" writer from Belgium. The university professors who invited Mandel claimed that the attorney general's decision deprived them of their First Amendment right to hear Mandel speak. The Supreme Court sided with the government, holding that 1) Congress had "plenary power to exclude aliens or prescribe the conditions for their entry into this country"; and 2) in the law Congress had delegated that power to the executive branch; and 3) when the attorney general decides "for a legitimate and bona fide reason" not to admit someone, "courts will not look behind his decision." That was the core of the three dissenters' argument. Judge Paul Niemeyer, the George H.W. Bush appointee, wrote that the majority was wrong to refuse to apply the Mandel precedent, and had thereby "fabricat[ed] a new proposition of law -- indeed, a new rule -- that provides for the consideration of campaign statements to recast a later-issued executive order." The result, Niemeyer wrote was a decision "radically extending" Supreme Court precedents in religion cases. Niemeyer and the two other dissenters, said Yoo, "urge the traditional deference that the courts have paid to the elected branches on national security and immigration matters." As for the majority: Quote: The court's approach here is unprecedented. Federal judges have never before questioned the motive behind a president's order, which was otherwise valid on its face. Trump, on the other hand, has given courts the material -- also for first time -- to question the good faith of a presidential order. But the decision could hamstring future presidents. Courts could be forever in the business of testing the "real" purposes of presidential actions for invalid motives. No matter how they decide, such review could sap chief executives of the speed and decisiveness that are necessary to deal with national security threats. Almost immediately after the 4th Circuit ruling was announced Thursday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions said the Justice Department "strongly disagrees" with the decision and will seek review in the Supreme Court. Because the president's case is strong, and because the case broke down on partisan lines in the 4th Circuit, some observers feel confident Trump will prevail with a Supreme Court that has five Republican appointees and four Democratic appointees. But that confidence might be misplaced. First, it is true that the four Democrats on the Court are slam-dunk certain to vote against the president. Some Republicans are certain to vote for him. But the Court's perennial swing vote, Justice Anthony Kennedy, will be under enormous pressure from the usual quarters -- the New York Times, National Public Radio, etc. -- to show his essential goodness as a human being by voting against Donald Trump. And what about Neil Gorsuch? The justice that Gorsuch replaced, Antonin Scalia, would have blown the Fourth Circuit decision clear out of the water. But Gorsuch is a question mark. The dispute over the Trump executive order is being fought in the courts, but it is intensely political. The shortest short version of the case is: It's all about Trump. Given that, even if the law is clear, there's no telling what the Supreme Court will do. Bolded: Emphasis. But but but the 4th is conservative right...

And the above is why the Supreme Court will likely find the EO constitutional as written with the recommendation to explicitly state that religion must not be used as criteria when considering immigration requests. In all likelihood the judges in the 4th know how this is going to play out at the SC level and are really just delaying it and making a "protest" decision. It's unethical as that kind of political *** isn't supposed to be in the courts, but reality is what is it is. It's JFK and I ur um would like to ur umm tell you how I ur umm am happy ur umm about it !

Almos JFK birthday. And I miss the edit button everyday.

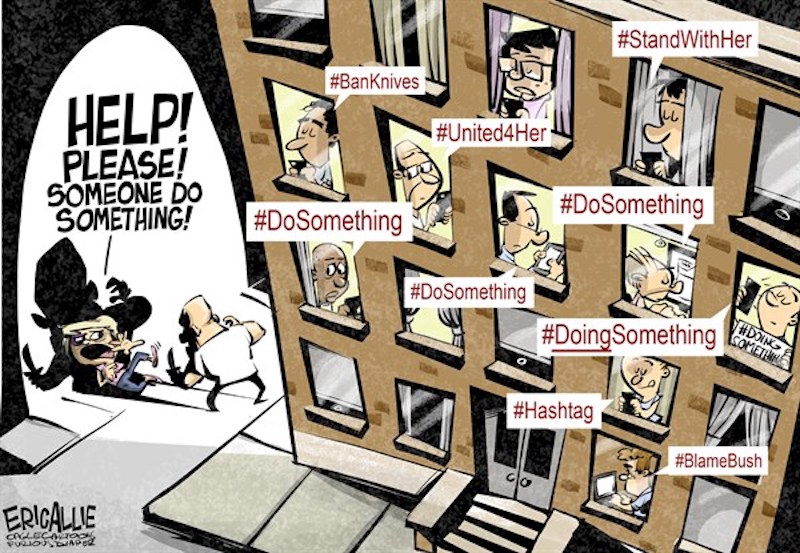

Here you guys go, the heart of the site's regressive leftists.

|

All FFXIV and FFXI content and images © 2002-2026 SQUARE ENIX CO., LTD.

FINAL FANTASY is a registered trademark of Square Enix Co., Ltd.